All

- All

- Agro and Allied

- Apparels

- Stoles & Shawls

- Wrap Around Skirt

- Art

- Baskets & Trays

- Basket

- Coasters

- Tray

- Curtains

- Custom Category

- Decor

- Cushion Cover

- Dining

- Dolls

- Interior Decor

- Lamp Shades

- Planter

- GI Products

- Gifts

- Brass Metal

- North East Hampers

- Souvenir

- Mulberry Silk Sarees

- Raw Materials

- Fabrics

- Yarn

- Smart loom

- Table Runner

- Uncategorized

- Sarees

- Cotton Sarees

- Eri Silk Sarees

- Muga and Tussar Silk Saree

- Accessories

- Earrings

- Handbags

- Neck Piece

0 item(s) - ₹0.00

0

Your shopping cart is empty!

Cotton Sarees

Purbashree's exquisite cotton sarees – radiant, elegant, and richly crafted with vibrant designs.

Shop Now

Muga & Tussar Silk Sarees

Purbashree's exquisite Muga Silk Sarees – lustrous, vibrant, and beautifully designed!

Shop Now

Eri Silk Natural Dye Stole

Purbashree presents handcrafted Eri Silk Natural Dye Stole - stylish, sustainable, and timeless

Shop NowBrowse Top Categories

Browse from our Cotton Saree

Made from: 100% pure Eri (ahimsa) silkLength: 5.5m (approx.), Width: 46" (approx.)Blouse Length: 1m (approx.)Color :&nbs..

₹14,999.00

Ex Tax:₹14,999.00Made from: 100% pure Cotton HandwovenLength: 5.5m (approx.), Width: 46" (approx.)Blouse Length: 1m (approx.)Color : Pink Ivor..

₹4,999.00

Ex Tax:₹4,999.00Made from: 100% pure Cotton HandwovenLength: 5.5m (approx.), Width: 46" (approx.)Blouse Length: 1m (approx.)Introducing our e..

₹4,999.00

Ex Tax:₹4,999.00Made from: 100% pure Cotton HandwovenLength: 5.5m (approx.), Width: 46" (approx.)Blouse Length: 1m (approx.)Color : Ivory Gre..

₹4,999.00

Ex Tax:₹4,999.00Made from: 100% pure Cotton HandwovenLength: 5.5m (approx.), Width: 46" (approx.)Blouse Length: 1m (approx.)Introducing our e..

₹4,999.00

Ex Tax:₹4,999.00Made from: 100% pure Cotton HandwovenLength: 5.5m (approx.), Width: 46" (approx.)Blouse Length: 1m (approx.)Introducing our e..

₹4,999.00

Ex Tax:₹4,999.00Made from: 100% pure Cotton HandwovenLength: 5.5m (approx.), Width: 46" (approx.)Blouse Length: 1m (approx.)Color : Pink..

₹4,999.00

Ex Tax:₹4,999.00Made from: 100% pure Cotton HandwovenLength: 5.5m (approx.), Width: 46" (approx.)Blouse Length: 1m (approx.)Color : Ivory Blu..

₹4,999.00

Ex Tax:₹4,999.00Accessories

Browse from our Accessories

The elegant and sturdy bamboo comb is ideal for all hair types and works great on wet or dry hair

It glides through the hair smoothly while massagi..

₹499.00

Ex Tax:₹499.00This Water Hyacinth Bag is totally handmade and out of natural fibres. If you are an ardent lover of handwoven and handicrafts, our Water Hyacinth Bag..

₹1,599.00

Ex Tax:₹1,599.00Beaded Fairy poppy Earrings by House of Macnok from the valleys of Pasighat, Arunachal Pradesh for Accessories lover. This earring will complement all..

₹699.00

Ex Tax:₹699.00Elegant Mopin Somin Earrings by House of Macnok from the valleys of Pasighat, Arunachal Pradesh for Accessories lover. This earring will complement al..

₹599.00

Ex Tax:₹599.00Basket

Browse from our Baskets

Extremly light weighted bamboo handcrafted round shaped fruit tray crafted by Assam crafters. This tray can be used for home decor or any utility purp..

₹249.00

Ex Tax:₹249.00Beautifully handcrafted green bamboo basket also called Changkhwai all the way from Meghalaya. This basket can be also used for other utility and deco..

₹399.00

Ex Tax:₹399.00Handwoven with utmost care and attention to detail, this bag is made from sustainable water hyacinth fibres, making it a perfect choice for environmen..

₹1,499.00

Ex Tax:₹1,499.00Our pure handmade green bamboo Basket is crafted to bring a sustainable vibe to your living style. Lightweight, durable, and easy to carry, it's made ..

₹499.00

Ex Tax:₹499.00Our pure handmade bamboo tray is crafted to bring a sustainable vibe to your living style. Lightweight, durable, and easy to carry, it's made from mat..

₹999.00

Ex Tax:₹999.00Our pure handmade bamboo Basket is crafted to bring a sustainable vibe to your living style. Lightweight, durable, and easy to carry, it's made from m..

₹499.00

Ex Tax:₹499.00

Browse from our Muga and Tussar Silk Sarees

Muga Silk - The most valued silk from India. Almost exclusively reared and produced in Assam, India. It is indigenous to the Brahmaputra Valley and as..

₹69,999.00

Ex Tax:₹69,999.00Muga Silk - The most valued silk from India. Almost exclusively reared and produced in Assam, India. It is indigenous to the Brahmaputra Valley and as..

₹59,999.00

Ex Tax:₹59,999.00Handwoven Assamese Tussar silk saree with traditional motifs handwoven in the looms of Assam.• Length x Width: 6.2 x 1.14 meters (46 inches) • Materia..

₹19,999.00

Ex Tax:₹19,999.00Handwoven Assamese Tussar silk saree with traditional motifs handwoven in the looms of Assam.• Length x Width: 6.2 x 1.14 meters (46 inches) • Materia..

₹19,999.00

Ex Tax:₹19,999.00Handwoven Assamese Muga x Tussar silk saree with traditional motifs of Assam. • Length x Width: 6.2 x 1.14 meters (46 inches) • Material: Silk • ..

₹25,000.00

Ex Tax:₹25,000.00Muga and Paat Silk - The most valued silk from India. Almost exclusively reared and produced in Assam, India. It is indigenous to the Brahmaputra Vall..

₹59,999.00

Ex Tax:₹59,999.00Muga Silk - The most valued silk from India. Almost exclusively reared and produced in Assam, India. It is indigenous to the Brahmaputra Valley and as..

₹44,999.00

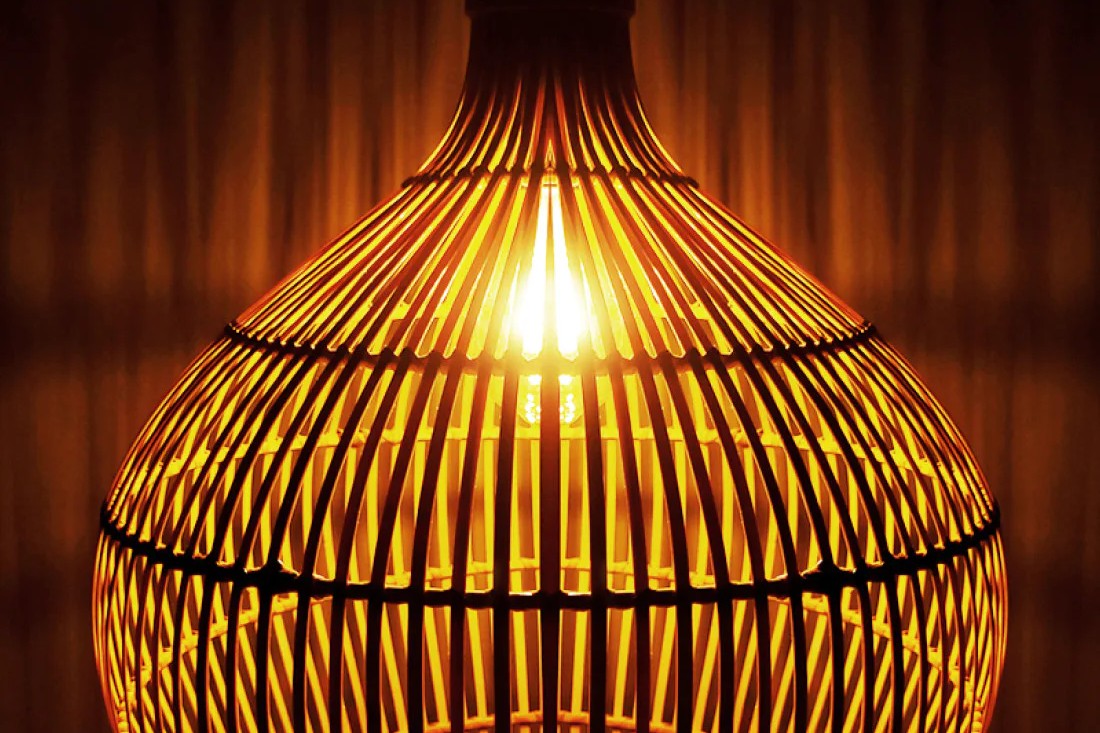

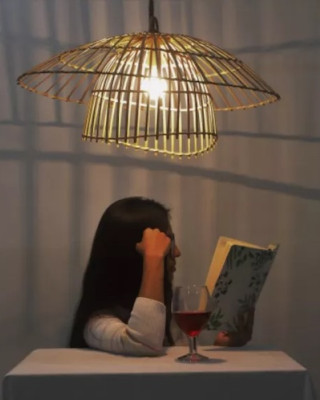

Ex Tax:₹44,999.00Lamp Shades

Browse from our Lamp Shades

Elevate your space with our exquisite Bamboo Lamp Shade Hanging, a captivating lighting fixture that seamlessly combines the beauty of nature with tim..

₹1,999.00

Ex Tax:₹1,999.00Lampshade completely handcrafted and made out of bamboo...

₹2,499.00

Ex Tax:₹2,499.00Lampshade completely handcrafted and made out of bamboo...

₹2,499.00

Ex Tax:₹2,499.00Lampshade completely handcrafted and made out of bamboo...

₹2,499.00

Ex Tax:₹2,499.00Elevate your space with our exquisite Bamboo LampShade Hanging, a captivating lighting fixture that seamlessly combines the beauty of nature with time..

₹2,499.00

Ex Tax:₹2,499.00Elevate your space with our exquisite Bamboo Lamp Shade Hanging, a captivating lighting fixture that seamlessly combines the beauty of nature with tim..

₹2,699.00

Ex Tax:₹2,699.00Elevate your space with our exquisite Bamboo Lamp Shade Hanging, a captivating lighting fixture that seamlessly combines the beauty of nature with tim..

₹2,499.00

Ex Tax:₹2,499.00Gifts

Browse from our Gifts

Handcrafted wooden souvenier of Assam dipicting the proud & heritage of Assam - One horn Rhino, Jaapi, Dhool & Pepa...

₹1,299.00

Ex Tax:₹1,299.00The bell-metal industry of Assam is the second-largest handicraft sector after bamboo craft. Bell-metal is an alloy of copper and tin and the craftsme..

₹1,599.00

Ex Tax:₹1,599.00

Browse from our Eri Silk Sarees

Made from: 100% pure Eri (ahimsa) silkLength: 5.5m (approx.), Width: 46" (approx.)Blouse Length: 1m (approx.)Color ..

₹14,999.00

Ex Tax:₹14,999.00Made from: 100% pure Eri (ahimsa) silkLength: 5.5m (approx.), Width: 46" (approx.)Blouse Length: 1m (approx.)Handwoven i..

₹15,999.00

Ex Tax:₹15,999.00Made from: 100% pure Eri (ahimsa) silkLength: 5.5m (approx.), Width: 46" (approx.)Blouse Length: 1m (approx.)Color :&nbs..

₹14,999.00

Ex Tax:₹14,999.00Made from: 100% pure Eri (ahimsa) silkLength: 5.5m (approx.), Width: 46" (approx.)Blouse Length: 1m (approx.)Introducing..

₹14,999.00

Ex Tax:₹14,999.00Made from: 100% pure Eri (ahimsa) silkLength: 5.5m (approx.), Width: 46" (approx.)Blouse Length: 1m (approx.)Introducing..

₹14,999.00

Ex Tax:₹14,999.00Made from: 100% pure Eri (ahimsa) silkLength: 5.5m (approx.), Width: 46" (approx.)Blouse Length: 1m (approx.)Introducing..

₹14,999.00

Ex Tax:₹14,999.00Made from: 100% pure Eri (ahimsa) silkLength: 5.5m (approx.), Width: 46" (approx.)Blouse Length: 1m (approx.)Color :&nbs..

₹11,999.00

Ex Tax:₹11,999.00New Arrivals

Made from: 100% pure Eri (ahimsa) silkDimensions: 90 x 220 cm approx.Handwoven in the looms of Assam Soft Can be styled with ..

₹1,999.00

Ex Tax:₹1,999.00Made from: 100% pure Eri (ahimsa) silkDimensions: 90 x 220 cm approx.Handwoven in the looms of Assam Soft Can be styled with ..

₹2,499.00

Ex Tax:₹2,499.00Made from: 100% pure Eri (ahimsa) silkDimensions: 90 x 220 cm approx.Handwoven in the looms of Assam Soft Can be styled with ..

₹4,999.00

Ex Tax:₹4,999.00Made from: 100% pure Eri (ahimsa) silkDimensions: 90 x 220 cm approx.Handwoven in the looms of Assam Soft Can be styled with ..

₹4,999.00

Ex Tax:₹4,999.00Made from: 100% pure Cotton HandwovenLength: 5.5m (approx.), Width: 46" (approx.)Blouse Length: 1m (approx.)Introducing our e..

₹6,300.00

Ex Tax:₹6,300.00Made from: 100% pure Cotton HandwovenLength: 5.5m (approx.), Width: 46" (approx.)Blouse Length: 1m (approx.)Introducing our e..

₹6,300.00

Ex Tax:₹6,300.00Made from: 100% pure Cotton HandwovenLength: 5.5m (approx.), Width: 46" (approx.)Blouse Length: 1m (approx.)Introducing our e..

₹6,300.00

Ex Tax:₹6,300.00Made from: 100% pure Cotton HandwovenLength: 5.5m (approx.), Width: 46" (approx.)Blouse Length: 1m (approx.)Introducing our e..

₹6,300.00

Ex Tax:₹6,300.00Wrap yourself in cultural finesse with our assam weave handloom cotton thread motifs stole. Intricately crafted, each motif tells a tale of Assamese a..

₹1,449.00

Ex Tax:₹1,449.00Handwoven by the weavers of Assam.Length: 1.9 x 0.6 meters (24 inches)• Material: Cotton• Warp x Weft : 100/2 cotton x 100/2 cotton..

₹1,399.00

Ex Tax:₹1,399.00The origin of muga silk is from Assam, it is generally believed that it was during the time of Ahom dynasty that muga silk is woven in the ..

₹12,040.00

Ex Tax:₹12,040.00Muga Silk - The most valued silk from India. Almost exclusively reared and produced in Assam, India. It is indigenous to the Brahmaputra Valley and as..

₹59,999.00

Ex Tax:₹59,999.00-586x88.png)

-320x400w.jpg)

-320x400.jpg)